What Did Vladimir Lenin Consider the Most Important Art Form in Shaping Opinion?

L iterature shaped the political civilisation of the Russian federation in which Vladimir Ilyich Lenin grew up. Explicitly political texts were difficult to publish nether the tsarist government. The rasher essayists were holed up in asylums until they "recovered": in other words, until they publicly recanted their views. Novels and poetry, meanwhile, were treated more than leniently – though non in every instance.

The principal censor was, of course, the tsar. In the example of Pushkin, the "father of the people", Nicholas I, insisted on reading many of his verses before they went to the printer. Some, as a result, were forbidden, others delayed, and the most subversive were destroyed by the frightened poet himself, fearful that his house might be raided. We will never know what the burnt verses of Eugene Onegin contained.

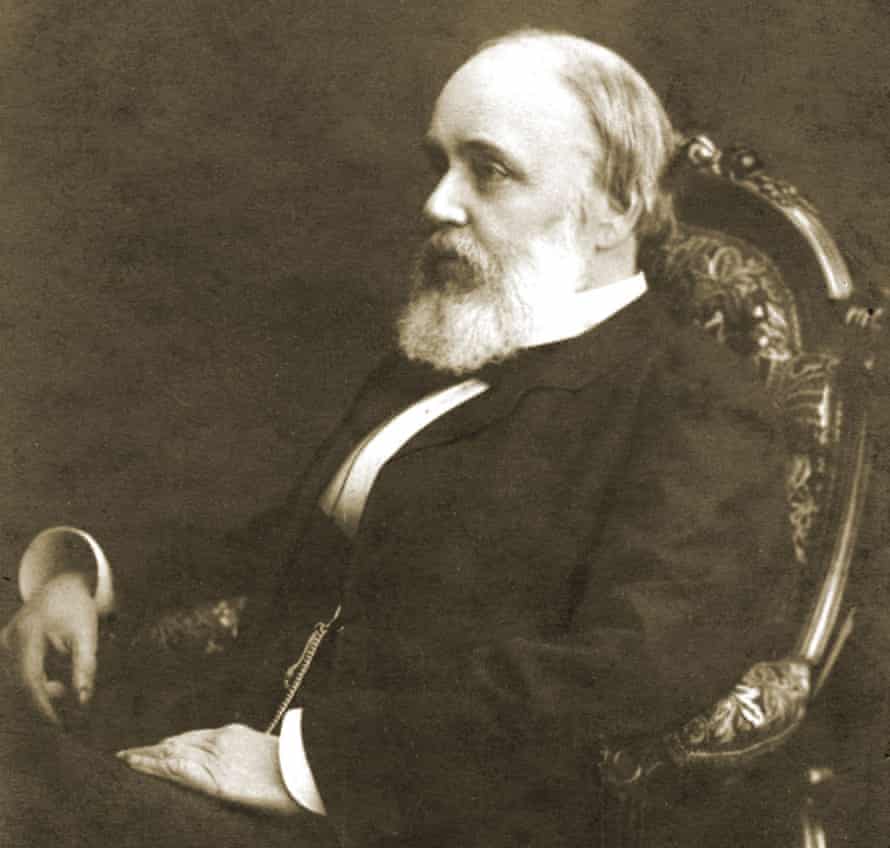

Nonetheless, politics by other means and in a multifariousness of unlike registers permeated Russian fiction in a manner without parallel in any other European state. As far as politicised literature and literary criticism went, the Russian intelligentsia were spoilt for selection. They devoured the acrimonious conflict between the powerful critic Vissarion Belinsky and the dramatist and novelist Nikolai Gogol, whose cut 1842 satire Dead Souls had invigorated the country and been read aloud to the illiterate.

Success, even so, proved to exist Gogol's undoing. In a subsequent piece of work, he recanted, writing of stench-ridden peasants and defending illiteracy. In the preface to the 2d edition of Dead Souls, he wrote: "Much in this book has been written wrongly, not equally things are actually happening in the land of Russian federation. I ask y'all, dear reader, to correct me. Practise not spurn this matter. I enquire you to do information technology."

Angered, Belinsky bankrupt publicly with him in 1847. Belinsky'due south widely circulated "Alphabetic character to Gogol" gave the recipient a long, sleepless dark:

I know the Russian public a little. Your book alarmed me by the possibility of its exercising a bad influence on the government and the censorship, just not on the public. When it was rumoured in St Petersburg that the authorities intended to publish your book [ Selected Passages from Correspondence With Friends] in many thousands of copies and to sell information technology at an extremely depression cost, my friends grew despondent; only I told them then and in that location that the book, despite everything, would have no success and that information technology would before long be forgotten. In fact it is now better remembered for the articles that have been written near it than for the volume itself. Yeah, the Russian has a deep, though withal undeveloped, instinct for truth.

In subsequently years, critics became much more cruel, lambasting novelists and playwrights whose piece of work they considered to be comparatively empowering.

This, and so, was the intellectual atmosphere in which Lenin came of age. His male parent, a highly cultured conservative, was the chief inspector of schools in his region and much respected every bit an educationalist. At habitation, Shakespeare, Goethe and Pushkin, among others, were read aloud on Lord's day afternoons. It was impossible for the Ulyanov family – "Lenin" was a pseudonym adopted to outwit the tsarist undercover police – to escape high civilisation.

At high school, Lenin fell in love with Latin. His headteacher had high hopes that he might become a philologist and Latin scholar. History willed otherwise, but Lenin's passion for Latin, and sense of taste for the classics, never left him. He read Virgil, Ovid, Horace and Juvenal in the original, likewise equally Roman senatorial orations. He devoured Goethe during his two decades in exile, reading and rereading Faust many times.

Lenin put his knowledge of the classics to skillful use in the fourth dimension leading upward to the October revolution of 1917. In April of that yr, he broke with Russian social-democratic orthodoxy and, in a set of radical theses, called for a socialist revolution in Russia. A number of his ain close comrades denounced him. In a sharp riposte, Lenin quoted Mephistopheles from Goethe's masterwork: "Theory, my friend, is grey, only green is the eternal tree of life."

Lenin knew better than virtually that classical Russian literature had e'er been infused with politics. Even the nearly "apolitical" of writers had establish it difficult to muffle their antipathy for the state of the country. Ivan Goncharov'due south novel Oblomov was a case in betoken. Lenin loved this work. It depicted the inertia, indolence and emptiness of the landed gentry. The book's success was celebrated by the entry of a new word into the Russian lexicon: oblomovism, which became a term of abuse for the course that helped the autocracy survive for so long. Lenin would later on argue that this disease was non confined to the upper classes alone, but had infected large sections of the tsarist bureaucracy and filtered down. Even Bolshevik apparatchiks were not immune. This was a case where the mirror held upwardly past Goncharov really did reverberate order at large. In his polemics, Lenin ofttimes attacked his opponents past comparison them to almost always unpleasant and sometimes minor characters drawn from Russian fiction.

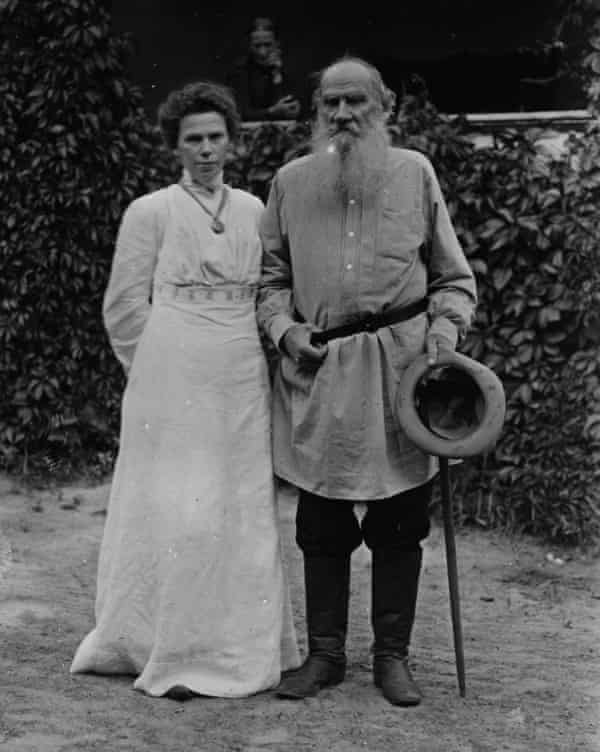

Where the state's writers differed (and they were non alone in this, of class) was on the means necessary to topple the regime. Pushkin supported the 1825 Decembrist uprising that challenged the succession of Nicholas I. Gogol satirised the oppressions of serfdom before rapidly retreating. Turgenev was critical of tsarism but disliked intensely the nihilists who preached terror. Dostoevsky's amour with anarcho-terrorism was transformed into its stunted opposite after a terrible murder in St Petersburg. Tolstoy'southward assault on Russian absolutism delighted Lenin, but the count'south mystical Christianity and pacifism left him common cold. How, Lenin asked, could such a gifted author be a revolutionary and a reactionary at the same time? Over the grade of one-half a dozen manufactures, Lenin unpicked the deep contradictions at play in Tolstoy's work. Lenin's Tolstoy was capable of providing a lucid diagnosis – his novels recognised and expressed the economical exploitation and collective anger of the peasants – but not of formulating a cure. Instead of imagining a properly revolutionary hereafter, Tolstoy had sought consolation in the utopian image of a simpler, Christian by. In "Leo Tolstoy as the Mirror of the Russian Revolution", Lenin wrote that "the contradictions in Tolstoy'southward views and doctrines are not accidental; they express the contradictory weather condition of Russian life in the last third of the 19th century". Tolstoy's contradictions thus served as a useful guide for Lenin'southward political analysis.

Meanwhile, Lenin was repelled by Dostoevsky's "cult of suffering", though the power of his writing was undeniable. Lenin's views on literature did not, however, become state policy. Only under a year later on the revolution, on two August 1918, the newspaper Izvestia published a listing of people, nominated by readers, to whom monuments were proposed. Dostoevsky was second, after Tolstoy. The monument was unveiled in Moscow in Nov of that year by the representative of the Moscow Soviet, with a tribute past the symbolist poet Vyacheslav Ivanov.

The writer who had perhaps the strongest impact on Lenin – on, indeed, an entire generation of radicals and revolutionaries – was Nikolay Chernyshevsky. Chernyshevsky was the son of a priest, as well as a materialist philosopher and socialist. His utopian novel What Is to Be Done? was written in the Peter and Paul Fortress in St Petersburg, where he had been incarcerated because of his political behavior. What Is to Exist Done? became the bible of a new generation. The fact that information technology had been smuggled out of prison gave it an added aura. This was the book that radicalised Lenin, long earlier he encountered Marx (with whom Chernyshevsky had exchanged letters). Equally a homage to the old radical populist, Lenin titled his first major political work, written and published in 1902, What Is to Be Done?

The enormous success of Chernyshevsky'due south novel greatly irritated the established novelists, Turgenev in particular, who attacked the volume viciously. This bile was countered with a burning lash of nettles from the radical critics Dobrolyubov (regarded by students as "our Diderot") and Pisarev. Turgenev was livid. Encountering Chernyshevsky at a public event, he shouted: "You're a snake and that Dobrolyubov is a rattlesnake."

What of the novel that was the subject field of so much controversy? Over the last 50 years I have made three attempts to read every single page, and all three attempts accept failed. Information technology is non a classic of Russian literature. It was of its time and played a crucial office in the post-terrorist stage of the Russian intelligentsia. It is undoubtedly very radical on every forepart, especially gender equality and relations between men and women, merely likewise on how to struggle, how to delineate the enemy and how to live by sure rules.

Vladimir Nabokov loathed Chernyshevsky only found information technology impossible to ignore him. In his concluding Russian novel, The Souvenir, he devoted 50 pages to belittling and mocking the writer and his circumvolve, but admitted that at that place "was quite definitively a smack of course arrogance about the attitudes of gimmicky well-built-in writers towards the plebeian Chernyshevsky" and, in private, that "Tolstoy and Turgenev called him the 'bed-issues stinking gentleman' … and jeered at him in all kinds of ways".

Their jeers were partly born of jealousy, since the subject of their snobbery was extremely popular with the young, and built-in besides, in the case of Turgenev, of a deep and ingrained political hostility to a writer who wanted a revolution to destroy the landed estates and distribute the land to the peasants.

Lenin used to go cross with immature Bolsheviks visiting him in exile, during the inter-revolutionary years between 1905 and 1917, when they teased him about Chernyshevsky'south volume and told him it was unreadable. They were too young to appreciate its depth and vision, he retorted. They should wait till they were 40. Then they would understand that Chernyshevsky's philosophy was based on simple facts: nosotros were descended from the apes and not Adam and Eve; life was a short-lived biological process, hence the need to bring happiness to every individual. This was not possible in a world dominated by greed, hatred, war, egoism and class. That was why a social revolution was necessary. Past the time the immature Bolsheviks climbing Swiss mountains with Lenin were approaching 40, notwithstanding, the revolution had already taken identify. Chernyshevsky would now exist read largely by historians studying the development of Lenin'southward thought. Erudite party progressives happily moved on to Mayakovsky. Not Lenin.

The classicism that was so securely rooted in Lenin acted as a bulwark to seal him from the exciting new developments in fine art and literature that had both preceded and accompanied the revolution. Lenin constitute it hard to brand any accommodations to modernism in Russia or elsewhere. The piece of work of the artistic avant garde – Mayakovsky and the constructivists – was not to his taste.

In vain did the poets and artists tell him that they, too, loved Pushkin and Lermontov, but that they were also revolutionaries, challenging old fine art forms and producing something very different and new that was more in keeping with Bolshevism and the age of revolution. He only would non budge. They could write and paint whatever they wanted, but why should he be forced to capeesh information technology? Many of Lenin's colleagues were more than sympathetic to the new movements. Bukharin, Lunacharsky, Krupskaya, Kollontai and, to a sure degree, Trotsky understood how the revolutionary spark had opened up new vistas. There were conflicts, hesitations and contradictions within the avant garde equally well, and their supporter in the regime was Anatoly Lunacharsky at the People'due south Commissariat for Education, where Lenin's wife, Nadya Krupskaya, worked as well. Shortages of newspaper during the civil war led to fierce arguments. Should they publish propaganda leaflets or a new verse form by Mayakovsky? Lenin insisted on the showtime pick. Lunacharsky was convinced that Mayakovsky's poem would be far more than effective and, on this occasion, he won.

Lenin was also hostile to whatsoever notion of a "proletarian literature and art", insisting that the peaks of bourgeois culture (and its more aboriginal predecessors) could not be transcended by mechanical and dead formulae advanced in a country where the level of culture, in the broadest sense, was far too low. Shortcuts in this field would never work, something that was proved conclusively by the excremental "socialist realism" introduced in the bad years that followed Lenin'due south expiry. Creativity was numbed. The leap from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom, where the lives of all would exist shaped by reason, was never fabricated in the Soviet Matrimony – or, for that matter, anywhere else.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/25/lenin-love-literature-russian-revolution-soviet-union-goethe