Review Before the West Coast a Sports Civil Rights Story

Jackie Robinson (1919-1972) was the beginning African-American actor in modern major league baseball game. His debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April xv, 1947 ended approximately 60 years of baseball segregation. But Jackie Robinson's pathbreaking backbone and resistance started long before his career in professional baseball game.

Robinson, the grandson of a slave and the son of a sharecropper, was not only a baseball game player. In high school, he played shortstop and catcher on the baseball team, quarterback on the football team, and baby-sit on the basketball game team. He was also a member of the lawn tennis team and the track and field team, and won awards in the broad jump. In junior higher, he played basketball, football game, and baseball, and participated in the broad jump. Transferring to nearby University of California at Los Angeles, he became the school's first athlete to win varsity messages in iv sports: baseball, basketball, football and track.

How he got to that identify is an amazing and inspirational story.

The author begins by providing groundwork on what life was like for African Americans earlier the Ceremonious Rights Motion and resulting legislation in the 1960's. As she writes in the Author Note at the conclusion of the book:

These are the kinds of signs that Jackie Robinson and scores of other Americans of color faced every day:

We Want WHITE TENANTS IN OUR WHITE COMMUNITY

NO DOGS, NEGROES, MEXICANS

WAITING ROOM FOR COLORED Just, BY Lodge POLICE DEPT

THIS PART OF THE BUS FOR COLORED RACE

PUBLIC Pond Pool, WHITE ONLY

Furthermore, as the only black family on their street, the Robinson family was not welcomed by their neighbors, who petitioned them to motility. The author writes:

"Simply Jack'south mother, Mallie, wouldn't go. She made it clear to whatsoever and all that she was not agape and that she wouldn't allow anyone to treat her family badly. Mallie taught her children to stand for what was correct, fifty-fifty when that was difficult to do. Jack learned those lessons well."

Beingness a star athlete in higher did not protect Jack from racism. The author reports that his opponents on the football field used to get out of their way to hurt him, whether he had the ball or not. She observes:

"Even Jack'southward own teammates in one case used do every bit an excuse to tackle him so difficult that they severely sprained his knee."

Just he didn't dorsum down, on or off the field.

When Earth War Two broke out, Robinson was drafted and assigned to a segregated Regular army cavalry unit of measurement in Fort Riley, Kansas. He was accustomed into officer candidate school (OCS), and earned his second lieutenant's bars on January 28, 1943. [Few black applicants were admitted into OCS but afterwards protests by heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis (then stationed at Fort Riley) and the assistance of Truman Gibson (and so an assistant noncombatant aide to the Secretary of War), the black applicants were accepted into OCS.]

Upon finishing OCS, Robinson was transferred to Fort Hood, Texas, for further training. At that place, he joined the 761st "Blackness Panthers" Tank Battalion. Fort Hood had a bad reputation amidst blacks, not merely because of the segregation on the mail service but also because of the depth of racism in the neighboring towns.

The 761st Tank Battalion – of which second Lt. Jack Robinson was a member – was a segregated unit during World State of war Two.

In May 1944, as the writer recounts, the U.S. Army issued an order forbidding segregation on military posts and buses. Only compliance in the South was problematic.

On July 6, 1944, Robinson was riding a double-decker on the base of operations and sitting next to a young man officeholder's light-skinned wife. The driver instructed Robinson to move to a seat further back.

Robinson argued with the bus driver, and when he got off at his stop, the dispatcher joined in the altercation. A crowd formed and military policemen arrived. The MPs took Robinson to the station. John Vernon, an archivist at the National Archives (Prologue, Leap 2008), tells what happened next:

"…when they arrived at the station to run across with the camp'due south assistant provost marshal, a white MP ran up to the vehicle and excitedly inquired if they had 'the nigger lieutenant' with them. The utterance of this unexpected and especially offensive racial epithet served to set Robinson off and he threatened 'to break in ii' anyone, any their rank or status, who employed that word."

Robinson connected to testify "boldness" and received a court martial.

Jackie Robinson in his military uniform

The author writes:

"Jack knew the court-martial wouldn't accept happened if he had just moved to the back of the bus. He worried how this would affect his reputation and integrity. But Jack also knew he had done the right matter. Jack remembered what his mother taught him."

Robinson contacted the NAACP and sought publicity from the Negro press. He also wrote to the War Department. The white press picked up on the situation since Robinson was a well-known athlete from his days at UCLA. Higher-ups became worried about this "political dynamite."

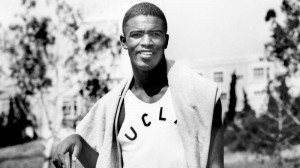

Jackie Robinson at UCLA

At the courtroom martial trial in August of that year, Robinson's commanding officer gave a glowing report on his character. His army-appointed defense attorney pointed out inconsistencies in witnesses' accounts. The attorney also suggested that Robinson'southward assertiveness was a legitimate expression of resentment given the racially hostile environment. Ultimately, the court acquitted Robinson of all charges.

While what happened to Robinson was not unique, the outcome of the disharmonize was unusual. It would more another decade before blacks were gratuitous to sit down where they chose on the bus. The author points out:

"Jack had fought for what he knew was right. He had stood upwardly to prejudice and discrimination and exercised his right to sit wherever he wanted on a motorcoach. He was one of the first black Americans to challenge a segregation law in court. And he won.

Jack made history that day."

The author concludes with a brief summary of Jack's life after the war, and the fact that he broke the color line in professional baseball.

At the back of the book, there is a timeline of Jack's life and of civil rights milestones, an Author Note, and a bibliography. In her Notation, the author observes that information technology took backbone of Jackie Robinson to "stand up to the racism that was entrenched and rooted deep in American culture…" only what she doesn't say is that he easily could have been lynched, and he knew that every bit well.

The illustrator, R. Gregory Christie, has won multiple awards for his piece of work, including the Coretta Scott King Illustrator Honor Accolade and the NAACP's Paradigm award. The pictures in this book are some of the most realistic I have seen him create. Just not totally. He still employs his trademark disproportionate compositions and elongated figures in his vivid gouache paintings. As he has stated in an interview, his art is meant to exist "a claiming for the viewer to break abroad from the established fundamental conventionalities that all children'southward books must be realistic or cute."

Evaluation: Many Americans know that Jackie Robinson was the get-go black role player in major league baseball, but not equally many know that his courageous resistance started long before that, or that Rosa Parks wasn't the starting time to reject to move to the back of the jitney. This inspirational story helps redress that omission.

Rating: 4/5

Published by Balzer + Bray, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2018

Source: https://rhapsodyinbooks.wordpress.com/2018/06/23/kid-lit-review-of-the-united-states-v-jackie-robinson-by-sudipta-bardhan-quallen/